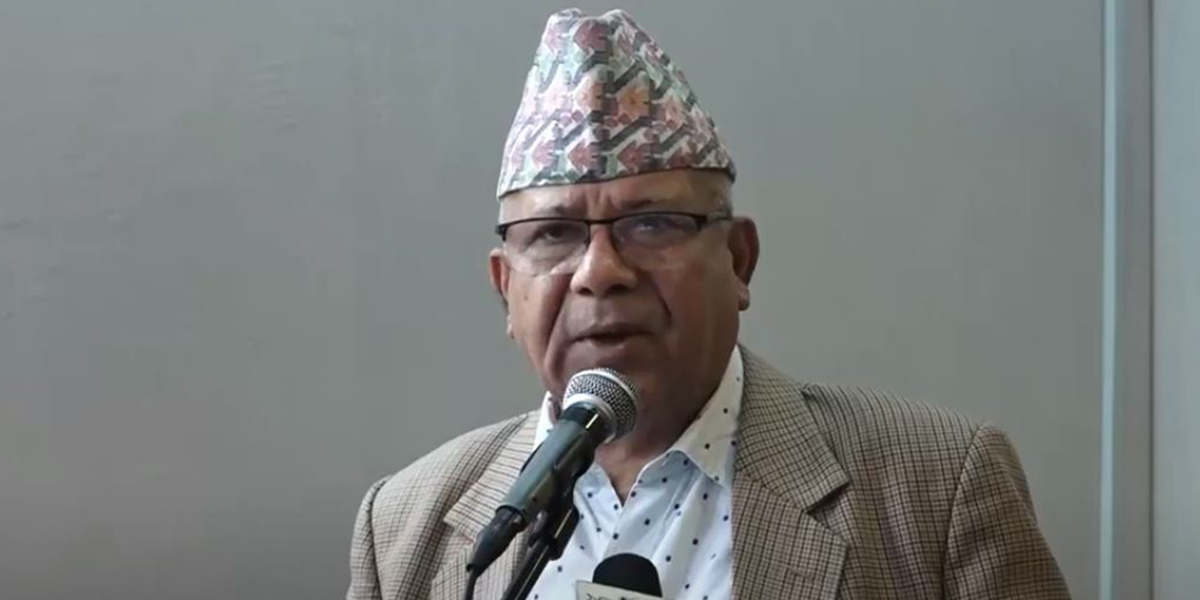

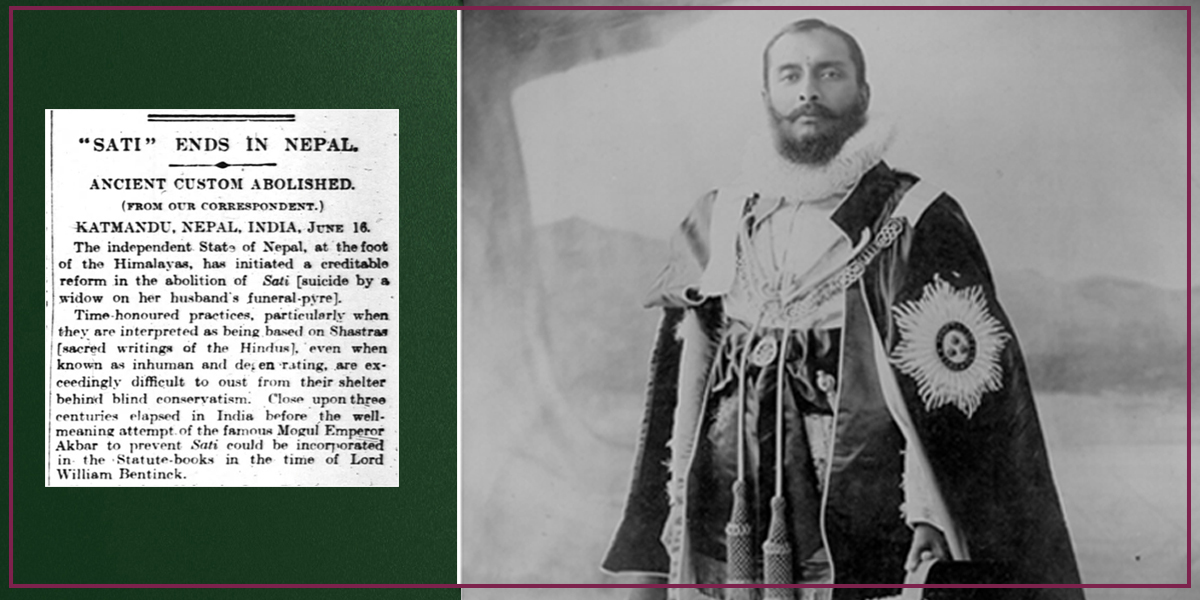

July 8 is the day Nepal abolished the practice of ‘Sati’. ‘Sati’ was a historical tradition where a widow would immolate herself on the funeral pyre of her deceased husband. This inhumane practice was prevalent in Nepal until the 1920s. Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher Rana, who was a ruler from the Rana dynasty, abolished the ‘Sati’ practice 103 years ago.

While previous rulers such as Jung Bahadur Rana, Ranoddip Singh, and Bir Shamsher had made some efforts to discourage the ‘Sati’ practice’ during their tenure, it was during Chandra Shamsher’s reign that significant steps were taken. He enacted a law that led to the meaningful abolition of the ‘Sati’ practice in Nepal.

Jung Bahadur Rana, the founder of the Rana dynasty, held a strong opposition to the practice of ‘Sati’ even before he assumed power. During the reign of Mathbar Singh Thapa, Jung Bahadur’s cousin Devi Bahadur received a death sentence. Despite Jung Bahadur’s efforts to prevent Devi Bahadur’s execution, his attempts were unsuccessful. Likewise, he made every possible effort to dissuade Devi Bahadur’s wife from committing ‘Sati,’ but his persuasion was in vain. (Life of Maharaja Sir Jung Bahadur Rana by Padma Jung Rana). This shows Jung Bahadur was against the practice of ‘Sati.’

After ascending to power, Jung Bahadur continued to take a stand against ‘Sati’ practice. He successfully intervened to prevent the wives of his nephew and a captain from committing ‘Sati’. (Sati practice in Nepal – Surya Bikram Gyawali, published in Gorkha Sansar Weekly, February 8-15, 1927, the mouthpiece of the Gorkha League based in Dehradun) These incidents further illustrate Jung Bahadur Rana’s firm stance against the practice of ‘Sati.’

Jung Bahadur Rana implemented provisions in the Civil Code issued in 1851 to discourage the practice of ‘Sati.’ Under the Civil Code, women who were under 16 years of age, pregnant, or had been married twice were prohibited from committing ‘Sati.’ Additionally, if a woman’s son was below 16 years of age or her daughter was below five years of age, she could not be forced to the ‘Sati’ practice. Furthermore, if a woman attempting ‘Sati’ couldn’t bear the pain and wished to escape from the funeral pyre, she was allowed to return home after performing a certain ritual. (Life of Maharaja Sir Jung Bahadur Rana by Padma Jung Rana) When Jung Bahadur’s brother Bam Bahadur passed away in 1857, he prevented his brother’s wife from committing ‘Sati.’ Similarly, he intervened to prevent his brother Krishna Bahadur’s wife and his own daughter from committing ‘Sati.’

Jung Bahadur Rana made serious efforts to discourage the practice of ‘Sati’. There are no records of women from the royal family and high-ranking officers committing ‘Sati’ during his tenure, indicating the effectiveness of his measures. However, the fact that three of his wives committed ‘Sati’ after his death suggests that his efforts were not completely successful.

According to accounts by Jung Bahadur’s son, Padma Jung, who was present at the cremation site in Pattharghatta, his father’s eldest wife and two other wives chose to commit ‘Sati’.

When news of the three wives of Jung Bahadur committing ‘Sati’ reached British Queen Victoria, she took the matter seriously. She was deeply moved by the news, maybe because she had personally met Jung Bahadur. In order to prevent further instances of women taking their own lives in this manner, Queen Victoria issued directives to the Governor General in Calcutta and the British Resident in Nepal to exercise greater caution.

As part of their duties, the British Resident in Nepal would send reports to the Governor General in Calcutta after every cremation that took place near the Pashupatinath Temple. This reporting practice allowed for monitoring and recording of such incidents. The British Resident became particularly vigilant when members of the royal family and Rana rulers were taken to the Pashupatinath Temple for their final days. They would often advise Prime Ministers to take measures to prevent women from committing ‘Sati’.

The eight-year reign of Ranoddip Singh, who succeeded Jung Bahadur, saw the deaths of Kings Rajendra Bikram and Surendra Bikram, and Crown Prince Trailokya. Likewise, Commander in Chief Jagat Shamsher and Dhir Shamsher, also passed away. Ranoddip Singh made notable efforts to prevent their wives from committing ‘Sati,’ which marked a significant milestone in Nepal’s ongoing campaign to abolish the practice.

The historical correspondence between British Residents and Nepal’s kings and prime ministers reveals the challenges faced in attempting to prevent women from practicing ‘Sati’. However, the fact that women from high-ranking families were not committing ‘Sati’ likely sent a positive message to the wider Nepali citizens, further promoting the movement against the practice.

The wives of Prime Minister Ranoddip Singh, as well as Jung Bahadur’s son Jagat Jung and grandson Yuddha Pratap Jang, did not commit ‘Sati’. Bir Shamsher, who succeeded Ranoddip Singh, introduced provisions related to ‘Sati’ in the Muluki Ain and issued Rules on the Abolition of ‘Sati’ Practice in 1887. These provisions included preventing pregnant women and new mothers from committing ‘Sati,’ even if they expressed a desire to do so. When Bir Shamsher’s brother, Commander in Chief Rana Shamsher, passed away, his wife also did not commit ‘Sati.’

Coming from the times of Jung Bahadur to Bir Shamsher, awareness about the practice of ‘Sati’ was increasing gradually. As the wives of ruling class individuals refrained from committing ‘Sati,’ it had a positive influence on society, leading to a decline in the practice over time.

By the time Chandra Shamsher came into power, the groundwork for the abolition of the practice of ‘Sati’ had been laid. Chandra Shamsher enacted a law on July 8, 1920, to completely abolish the practice of ‘Sati.’ Under this Act, individuals who provoked or forced women to commit ‘Sati’ could be charged with murder. Prior to the implementation of this law, some people would exploit the practice of ‘Sati’ for personal gain or to acquire the property of the women involved.

Before enacting the law to abolish the practice of ‘Sati’, Chandra Shamsher convened a council meeting with priests and palace officials. During the meeting, it was concluded that women who maintain a virtuous life after the death of their husbands would attain the same afterlife as those who practiced ‘Sati’.

Five years later, in November 1924, Chandra Shamsher took another significant step by abolishing slavery in Nepal. The decision came into force in 1925. These reforms, both the abolition of ‘Sati’ and slavery, were considered groundbreaking and progressive during that era.

Chandra Shamsher’s reform efforts gained recognition even in the Western media. Some universities in the United States proposed to confer him with honorary PhDs in appreciation of his progressive works. However, Chandra Shamsher did not express interest in accepting these honorary degrees, possibly because he had already received an honorary PhD from the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom in 1908.