KATHMANDU: The feeling of exhaustion that comes from not being able to fulfill childhood dreams keeps haunting people for a long time. It is common to hear people lamenting the failure to materialize their childhood dreams. Rama Mishra from Chitwan shares a similar dissatisfaction with life. Her childhood dream was to become a teacher. She remembers her mother telling her, “The person who teaches in college is the greatest person.” This statement became her guiding principle and the young girl decided then that she would become a professor.

“I remember asking my mother what I needed to do to become a lecturer,” Rama recalled. Her mother advised her to first obtain a degree (Masters). Even though she was just eight years old and didn’t know what a “degree” was, she was determined to achieve her goal. “I decided then and there, I will get a degree and become a teacher.”

After completing high school, Rama pursued studies in the science faculty and earned a bachelor’s degree in Biology. She went on to obtain her Masters in Zoology and started teaching while studying. She felt proud when her parents greeted her with “Namaste,” and her hard work was recognized when she received an award for the best teacher in a school. Despite these accomplishments, she had her sights set on becoming a college lecturer.

However, an orientation program presented an opportunity for Rama to make a U-turn in her career. “During the program, I realized that I hadn’t learned enough,” she said. This realization prompted her to pursue a Masters in Zoology, and she subsequently decided to pursue a PhD as well.

Chasing Cats

During Rama’s second year of post-graduation, a group of graduate students from an Australian university came to Chitwan. Six Nepali students accompanied them on a field trip. Rama was one of them. “Being with them gave me the opportunity to learn about experimental methods and techniques for researching small mammals, small cats, birds, and insects,” she said. “I enjoyed teaching, but being with them made me realize that there was another part of me that I could enjoy as well.”

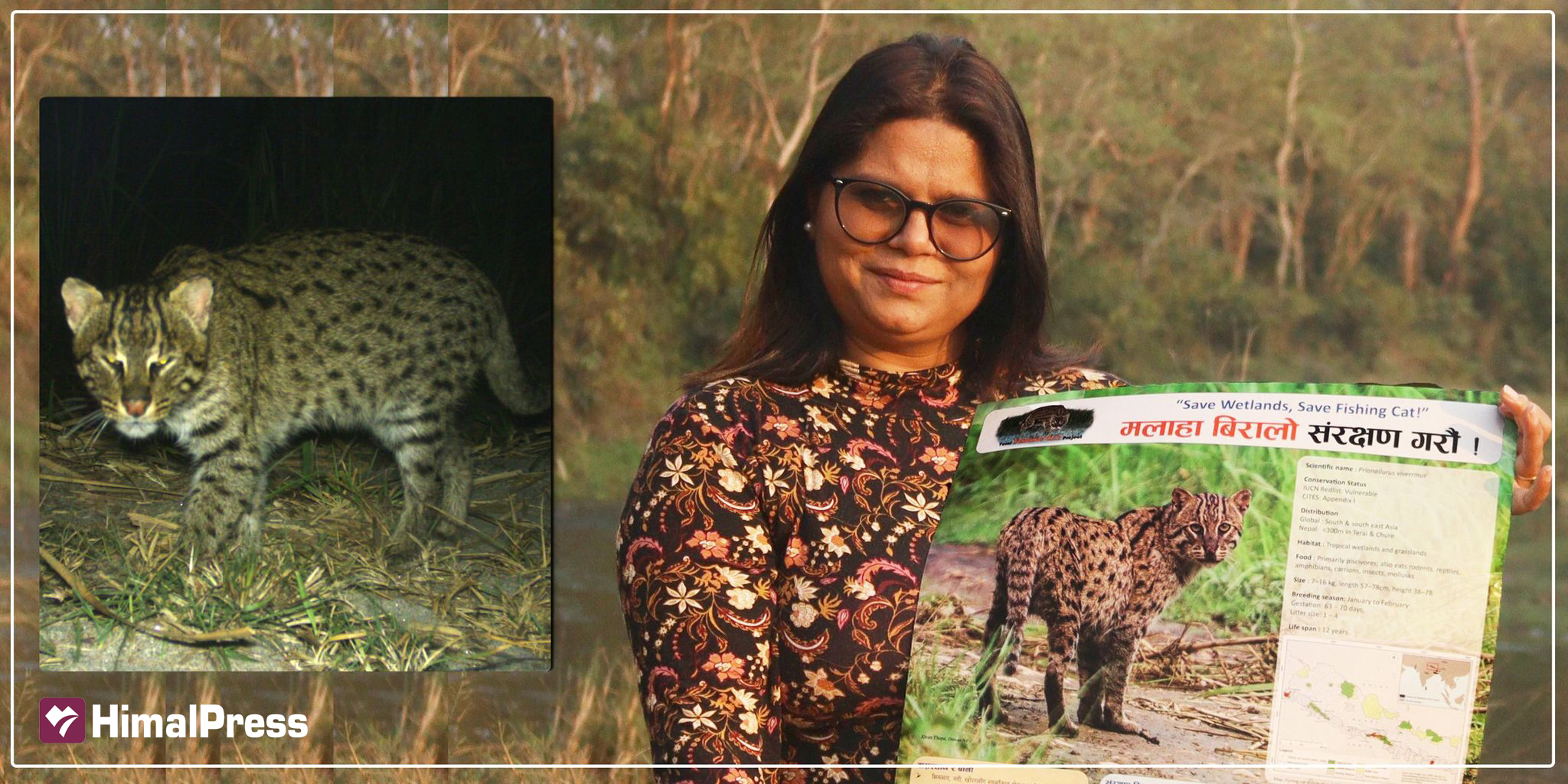

Her attention was drawn to fishing cats. In 2012, she wrote her Masters thesis on these small mammals. At that time, the Nepal Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC) was implementing a fishing cat project in Sauraha. “I was the first in Nepal to do a thesis on fishing cats,” she said. She selected some wetlands in Chitwan and collected data through camera trapping. She has since presented her research in both national and international programs.

Many don’t know about the fishing cat

Although Rama successfully conveyed the message that a thesis could be done on small mammals, she faced many difficulties during her research. “Many people would ask whether fishing cat was a fish or a cat. At that time, many people didn’t know what a fishing cat was,” she added.

The questionnaire she had prepared for the survey didn’t work with ordinary people. So, she conducted a different kind of survey with the help of a nature guide who had worked in Chitwan Park for 10 years. “I realized that research alone wouldn’t accomplish anything significant. I needed to first make people aware of what a fishing cat is and encourage them to protect it,” she added.

Currently, Rama is pursuing her PhD on fishing cats. Additionally, she has also started working on a fishing cat project in Tarai.

Lack of Study

There are not sufficient studies on fishing cats at both national and international levels. “If a tiger dies, it becomes a topic of news. But when other cats die, nobody cares,” she said. Therefore, no one has data about fishing cat population in Nepal.

In 2012, 25 fishing cats were found in Chitwan National Park, and 20 were spotted in Koshi Tappu Wildlife Conservation Area in 2017. “We have only observed them in protected areas. We have yet to spot a fishing cat outside of these areas,” she said. “We only know that they are endangered.”

Without adequate studies, it is challenging to create a conservation plan. Studies conducted so far have shown that less than five percent of land area is suitable for this cat species.

Human encroachment biggest threat

Rama believes that human beings pose the greatest threat to fishing cats. “They are in crisis due to human encroachment,” she said. Most people in aquaculture business mistake them for domestic cats and use traps to kill them. It is estimated that 65% of their habitat is outside protected areas, where human activity is prevalent.

The young researcher believes that changing people’s attitudes towards fishing cats is crucial to their survival. “These cats are found in areas where they can easily hide,” she said, adding: “Especially in bushes like reeds and bamboo.” They are mostly found around fish ponds, as long as there is enough hiding space. They have also been seen in sugarcane fields near water bodies.”

Rama says that fishing cats are adapting to their changing environment to survive. “They are using paddy, wheat, corn, and sugarcane fields as their habitat,” she said. “The places where people roam are not their permanent habitat.”

Why protect fishing cats?

There are 40 species of cats in the world, out of which 13 cat species are found in Nepal. Fishing cats are exclusively found in wetlands and around water bodies. “They play an important role in controlling the natural enemies of wetlands and agricultural areas,” said Rama, “Rats eat paddy and cause loss to farmers, and fishing cats control these rats. If there were no fishing cats, the balance of the wetland ecosystem would be disturbed.”

To protect fishing cats, attention should be paid to improving their habitat and managing wetlands and grasslands. Rama believes it is crucial for everyone to understand that fishing cats do not harm people but only benefit them.

“Why protect these cats?” some people ask Rama. “These cats should be protected for the entire environment. Human beings must protect fishing cats to live in a healthy environment,” she explains. She also believes that the government should encourage those who are involved in fishing cat protection.

Rama informed that the conservation community celebrates ‘Fishing Cat February’ to raise awareness about fishing cats. She has traveled from Jhapa in the east to Mahendranagar in the west to study fishing cats.

“Since it’s not possible for one person to reach all the places, we have conducted various training programs for students and locals,” she said. “We have also assigned volunteers in Tarai districts.”

Along with fishing cats, Rama wishes to work on the protection of nine other species of small cats.

Fishing cats are usually found in places up to 300 meters above sea level, but in Sri Lanka, they have been found at places up to 1,600 meters. “Fishing cats are found in eight countries, including Nepal, India, and Pakistan. Sadly, this species has gone extinct in many countries. In some places, they may have disappeared without being discovered,” she added.

Women in conservation

Until a few years ago, the number of women involved in conservation work was very low. Recognizing this, Rama has encouraged more and more women to join the ‘Tarai Fishing Cat Project’. “We aimed for at least 50% women, but nearly 70% are women,” she said.

She believes that the general public’s view of women has changed recently. When Rama conducted the first community program on elephant conservation in Madi, Chitwan, she remembers local women saying: “Women haven’t been involved in conservation work before, please come again.”

“It takes a long time to change mindsets, you have to be patient,” she added.

But she is happy to see an increase in women’s participation in conservation. “When I started in conservation, people would ask me if I was married or single,” she said. “Some even said it’s easier for me to pursue a PhD as my husband is also in the conservation sector. They think women are not capable. Every woman has her own struggle.”

Rama got married while doing her Master’s thesis. After marriage, she had to balance her family and career. She started working as a freelancer. “Many people don’t understand this aspect of women’s lives. They ask why you have to work when your husband is taking care of you. Men aren’t asked such questions,” she added.

Rama says that women, like men, are hardworking and capable. She is an example of that herself. While pregnant, she tied her stomach with a cloth and went to Bara, Saptari, Rautahat, Sunsari, and other districts for work. In that situation, some accused her of being careless while going for fieldwork.

“It wasn’t carelessness. It was my passion for my work,” she said. “Who doesn’t like to take care of their health?” She continued her work despite the various challenges of pregnancy. Her second child was born seven months into her pregnancy. “I gave birth within a week of returning from the field,” she said.

Fulfilling her dream

Rama, who had dreamed of becoming a teacher since childhood, is still involved in teaching in various ways. She teaches conservation to students in various schools in Tarai and conducts training at the public level.

“Conservation work allows me to fulfill my teaching dream,” she added.