A mountain in the Rolwaling range in the Nepal Himalayas with minimal snow cover (Image: Ganga Raj Sunuwar / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

A mountain in the Rolwaling range in the Nepal Himalayas with minimal snow cover (Image: Ganga Raj Sunuwar / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA)

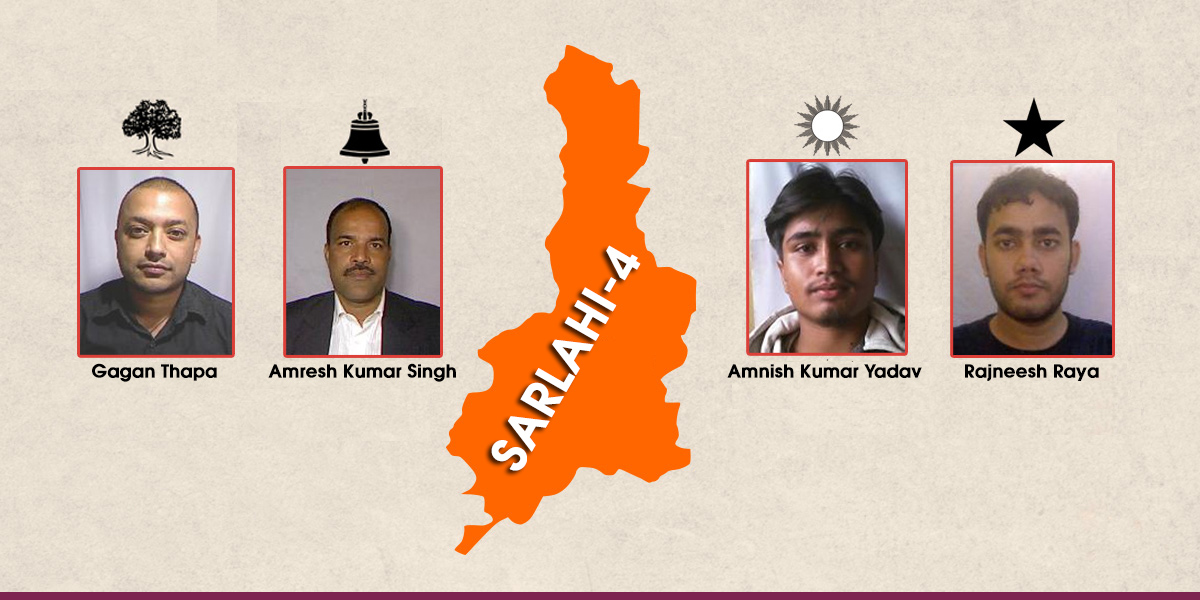

Over the first few weeks of 2026, intense snowstorms and freezing rain in the northern hemisphere caused major disruptions in power and transport across North America and Europe, resulting in over 60 deaths in the US alone. Yet in the southern part of the world, high-elevation areas such as the Himalayas have been experiencing “snow droughts”. Through December 2025 and much of January, parts of the mountain range were snowless, with no sign of a real winter in sight.

“The same pattern appears (with)in Asia: Kamchatka (in Russia) and Japan have received record snowfall, while the Tibetan Plateau has received much less,” Judah Cohen, a climatologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Dialogue Earth.

The warming of the earth has led to snow decreasing overall, but cold events may remain severe in some locations due to factors like disruptions to Arctic air regions, wrote Cohen and climate scientist Mathew Barlow. But in the Himalayas, this has not been the case recently.

Changes in large-scale wind and precipitation patterns have made the weather systems that bring winter rain and snow to the region increasingly erratic, disrupting their timing and reliability, and leading to lower-than-normal snowfall, said Sher Muhammad, the cryosphere monitoring lead at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD). Snowfall is also starting later in the winter season, with a shift to higher elevations, Muhammad told Dialogue Earth.

These changes in precipitation impact the glaciers on the Himalayas, and for the millions of people living downstream, the erratic snowfall could have severe impacts on their safety, water security, and livelihoods, experts told Dialogue Earth.

Snow is changing

Experts Dialogue Earth spoke to have attributed the lower snowfall in the Himalayas to its weather systems becoming more unpredictable.

The main source of winter precipitation in the Himalayas are western disturbances – storms originating in the Mediterranean region that bring moisture eastwards to the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent.

This weather system has brought snowfall to the western Himalayas this week, which includes the northern Indian areas of Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu & Kashmir. But these have been erratic, short, and heavy snowfall bursts which “may not fully compensate” for the snow deficit seen earlier this year at the catchment area of rivers fed by Himalayan snow, Muhammad said.

At the start of winter in December, large swathes of the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, in the western Himalayas, had been facing long dry spells with below-normal rain and snowfall.

Data from the India Meteorological Department (IMD) shows that winter precipitation in December 2025 was 99-100% below normal in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, 78% below normal in Jammu & Kashmir, and 63% below normal in Ladakh. In the Hindu Kush Himalayas, where winter precipitation is mainly in the form of snow, such deficits reflect an exceptionally weak snowfall season.

Precipitation in these areas and the rest of north-west India between January and March this year is also expected to be below normal. The IMD has forecast that the region will receive less than 86% of precipitation of the long-term averages of that period, taken between 1971 and 2020.

However, it is not just the total amount of snowfall that matters, Muhammad noted, but its timing, elevation, and persistence, or the duration snow stays on the ground without melting.

Over the past two decades, snow droughts, or periods of atypically low snow accumulation, have been increasing with concerning frequency in the Himalayas, according to the journal Nature. Last year was the third consecutive year of below-normal snow persistence, hitting a record low of 23.6% below normal, according to a report published by ICIMOD. Between 2003 and 2025, the region experienced 13 below-normal snow years, it noted.

Muhammad said that the western disturbance weather system’s behaviour is complex and has become increasingly difficult to predict with time. “There is no consistent long-term trend in their frequency,” he said. In the last few years, western disturbances have been facing delayed onset in some winters, and a shift towards short-duration, high-intensity events, he added.

“The region now swings rapidly between snow drought conditions and episodic heavy snowfall, leaving overall winter snow accumulation below normal,” Muhammad noted. There have also been longer breaks between western disturbances, which explains the dry conditions observed earlier this winter, he added.

Additionally, studies have acknowledged a lack of scientific consensus on how the weather system is impacted by climate change.

All of this is cause for concern, said Muhammad. “Variability is often more damaging than a steady shift, and it is much harder to manage unpredictable snow.” But he noted that the later snowfall, as well as the decreased snowfall in the Himalayan valley floor, is linked to climate change.

Less snow means less water

During warm winters, like the current season, storms that would have produced snow at mid-elevations of between 1,500-3,000 metres above sea level often create rain or mixed precipitation instead, Muhammad noted. Tourist hotspots such as Shimla, Manali, Mussoorie, and Nainital sit at this height. But areas with high elevations, such as Ladakh, still receive snow.

These changes in precipitation – of reduced and inconsistent snowfall – can lead to increased rain-on-snow events, Muhammad said. Such events often lead to the quick melting of snow, causing rapid flooding.

As rain-on-snow events increase, this reduces the natural reservoir function of seasonal snow and accelerates snowmelt, Muhammad said. Accelerated snowmelt is known to trigger hazards such as avalanches, landslides and downstream flood peaks

The precipitation changes are also expected to result in uncertainty on the availability and timing of meltwater in spring and early summer. The water stored as snow is crucial during these dry seasons in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, and water shortage could become an imminent issue for many sectors, including hydropower and irrigation, the BBC noted. This could have implications for the two billion people across Asia who depend on it for their livelihoods and survival.

For instance, farmers in northern Indian states like Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, who rely on winter snowmelt to irrigate crops before the monsoons, could be seriously affected. Untimely snowfall, or a lack thereof, can cause premature bud breaking, early flowering and infections in crops such as apples. In recent years, this has resulted in reduced yield and significantly affected farmers’ incomes.

In India, the water shortage issue is worsened by the sustained reduction in snowfall over the last two decades, said Manish Mehta, a scientist specialising in glaciology at the Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology. This reduction has been causing the annual snowline – above which snow is found on the ground year-round – to shift to higher elevations.

The shift has led to lower overall snow cover and earlier melting of the snow covering glacial surfaces, leading to premature melting of glacier ice by exposing more of its surface to warmer air and sunlight sooner in the year.

“Glaciers are melting even before the monsoon season begins, causing glacial retreat and a decrease in glacier mass and volume,” Mehta told Dialogue Earth.

In the early monsoon, river flows depend on the snowmelt, while during the peak of monsoon season, they depend on monsoon rains, Mehta explained. But during peak and late winter, the river flows depend on ice melt. Faster melting of glaciers will therefore affect the region’s long-term water security. Though impacts will not be seen immediately, “its effects will be visible in the long run, such as drying up of some rivers, drying up of waterfalls [and] reduced water flow [in the Hindu Kush Himalaya] due to melting of ice during the dry season”, he said.

Improving water management

To better manage water in the Himalayan region, Muhammad says there is a need to combine satellite data with more on-ground snow measurements across elevations to arrive at an estimate of how much water will be available when snow melts. Operational snow and runoff forecasts should also be used to plan reservoirs and irrigation channels.

There has been some progress in developing existing systems that capture erratic winter patterns, he said, such as NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectoradiometer (Modis) and national meteorological and hydrological services. But it hasn’t been enough to cover the gaps, he added, explaining that many mountain areas have few high-altitude observations.

While datasets from remote sensing satellites help, obstacles remain on the operational front, he noted. These include clouds, complex terrain, and the absence of short-term forecasts to issue early warnings for floods, avalanches, and glacial lake outburst floods.

Regionally, standardised methods and data exchange across transboundary basins are essential, because these water risks do not stop at national borders, Muhammad added. “It is extremely important to strengthen monitoring, forecasting, science-based decisions, and preparedness.”

This article was originally published on Dialogue Earth under the Creative Commons BY NC ND licence.

(Shalinee Kumari is Dialogue Earth’s South Asia editorial assistant, based in New Delhi.)