WHY NATIONS FAIL was a title which attracted audiences worldwide in 2013. The authors, Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson, have referred to Nepal several times—for all the wrong reasons. And most of the time, Nepal is bracketed along with Afghanistan and Haiti. In the intervening years, Americans found it expedient to leave Afghanistan in tatters. While the case of the Caribbean country of Haiti may appear different, decades of US interference have been directly responsible for where it stands today. Uncertainty, insecurity, and economic chaos in the aftermath of the assassination of the sitting president, in July 2021, are too visible to be overlooked. Neither has the UN presence been much of a help thus far.

Where does Nepal, the other nation mentioned in the book, stand a decade later? Readers would obviously express their curiosity. As the scenario unfolds, Nepal has witnessed profound changes in the past 10 years, but the country has become weaker—both politically and economically. While the revolutionary zeal of leaders, including those of Maoists’, have succeeded in displacing the monarchy and declared Nepal a republic, the erstwhile world’s only Hindu kingdom remains a land of instability and is being constantly watched by India and China. Both of them get naturally suspicious when a third power, the US, attempts to sneak into their neighborhood. And Nepal’s bewildered leadership continues to be unsure about their own response if a Ukraine-like situation unrolls in the Himalayan part of Asia.

Asset or Liability?

For decades, leaders within Nepal blamed the monarchy as the root cause of instability and underdevelopment. Successive leaderships in India too perceived an assertive monarchy on their northern border as a liability as each of the four kings since the 1950s remained recalcitrant, thereby maintaining a markedly different posture from the monarchy in adjoining Bhutan. At the turn of this century, New Delhi began to lend a helping hand to the Maoist rebels and other disgruntled leaders to get rid of the monarchy, without realizing its long-term effects on India itself. In a bid to make Nepal a pliant state, successive Indian leaderships unwittingly brought their regional rival China further closer to their northern border. Delhi now knows Beijing will react instantly and visibly if Tibet becomes a more disturbed territory.

That the institution of monarchy is essential for Nepal’s stability and unity was foreseen by the country’s charismatic leader BP Koirala as early as the 1970s. Although imprisoned by King Mahendra for eight years (1960-68) and forced to lead a life in exile for the next eight years, it was Koirala who argued for the continued retention of monarchy—in the British-style constitutional form. And since all senior leaders of the Nepali Congress regarded Koirala as their visionary leader, they accepted his plea to hold on to the monarchy for the larger interest of the country’s sovereignty as well as its distinct identity. Koirala’s determination was probably influenced by contemporary events in other parts of South Asia: Sikkim and Bangladesh, which Indians helped ‘liberate’ from Pakistan. But Nepali Congress leaders after Koirala’s death, in 1982, abandoned the ‘policy of national reconciliation’.

Explaining the Unexplained

Who would know Koirala’s political thoughts and farsightedness better than Ganesh Raj Sharma, the person who coordinated the publication of Koirala’s autobiography—Aatmavrittaanta—in 1998. Later, Sharma succinctly further explained some of Koirala’s policies in a series of articles he published in the Nepali language. Senior advocate Sharma passed away in October 2015.

Incidentally, I was fortunate to be introduced to Sharma, one of the country’s renowned constitutional lawyers, by none other than Koirala himself when I went to meet him at his Chabahil residence in 1979. “He is my lawyer who counsels me on court cases I’ve been facing,” Koirala told me, gesturing toward Sharma, who was sitting next to him. Fortunately, that formal acquaintance became the basis for a sustained friendliness. Earlier, I had met Koirala in London when BBC Nepali’s editor Mani Rana and I, as his colleague, went to interview him in the hotel he was staying at. He was on his way back from medical treatment in the US. During the interview, Koirala’s stated position on the Nepali monarchy was not different from what he had said upon return from exile in 1976.

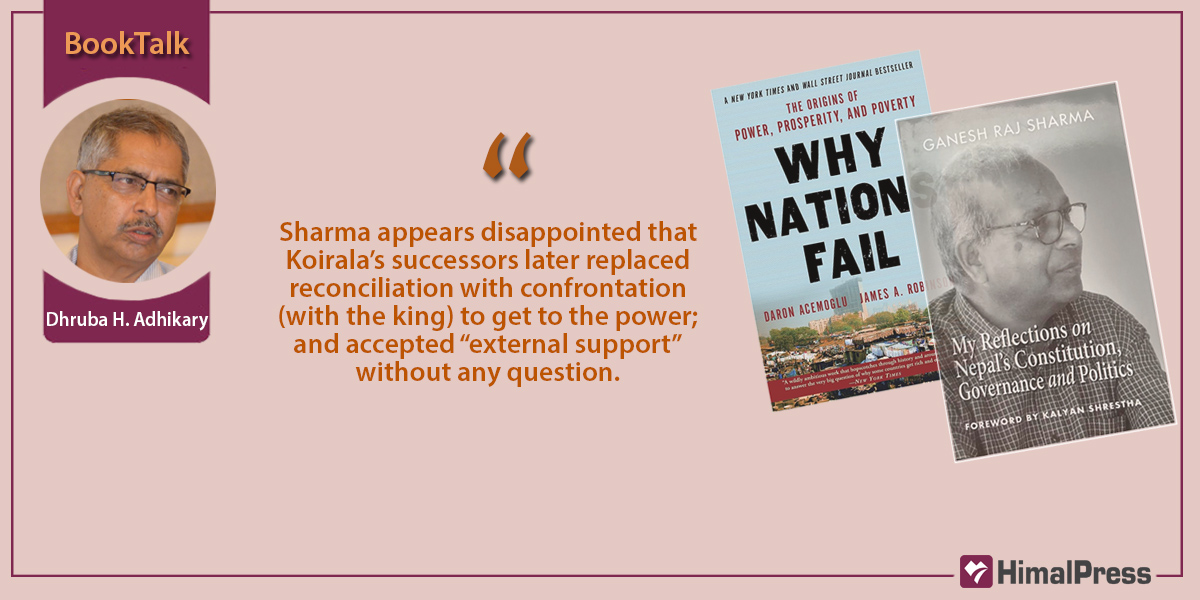

I recently got hold of a book with Sharma’s photo on the cover. It is a book in English containing some of his high-value ideas and analyses on the political and legal developments in post-1950 Nepal. In the Publisher’s Note, Madhab Lal Maharjan of the Mandala Book Point tells the readers how late Sharma’s daughter found a “systematically arranged folder” full of articles, in English, with an “unspoken intent of publishing them in a book form.” Maharjan happily agreed to publish this anthology of 238+ pages. This treatise offers 15 detailed write-ups with scholarly insights and analyses of events and trends that late Sharma witnessed in five decades of his active professional life. The topics under discussion range from democratic experiments in representation, the electoral system, constitutional reforms, the monarchy, the role of leadership, and a nation’s right to survive. The last topic of the book has this inquisitive headline: Nepal, India, and China: A Triangular Relation in Trial.

Meddlesome Neighbor

Sharma’s points of view on the monarchy in Nepal are discussed mainly in two chapters. The first one reads as follows: BP Koirala-Philosopher, Statesman, and Guide. In it, Sharma reveals an incident to narrate how Koirala was hurt by the unhelpful attitude of some of the Indian leaders regarding democratic innovation in neighboring Nepal. “Koirala told an emissary of Indira Gandhi that he would rather remain a subject of his king than serve India’s interest.” He knew about the possible implications of the bifurcation of Pakistan and annexation of Sikkim; developments that took place in the aftermath of India’s security treaty with the Soviet Union. Thus, it was but natural for Koirala to give priority to nationalism than anything else. The other chapter delves into the relevance of monarchy in Nepal’s democratic development. Sharma provides a number of angles to conclude that the monarchy is the “only institution that can be conceived of in both a traditional and heterogeneous nation”. Sharma appears disappointed that Koirala’s successors later replaced reconciliation with confrontation (with the king) to get to the power; and accepted “external support” without any question. Nevertheless, Sharma extols the main features of the 1990 constitution as it guaranteed the continuity of the monarchy. Today, without a doubt, Sharma would have been saddened if he were to survive to see the day revolutionaries, with the help of turncoat democrats, found it expedient to receive external support and then abolish the monarchy. The vacuum created thereafter is being filled in by the puppets the external powers promoted over the years. No sane person would expect a phase of national stability in these circumstances. It is only sober people who can think the way Sharma thinks: Loss of independence of a country will result in the loss of freedom of the individuals.

Finally

Readers of the present book are likely to look for more from Sharma’s pen as he may have left other folders with scripts in which he might have recorded even more important subjects. His close association with Koirala was one aspect, his extended audiences with King Birendra, for instance, may have more revealing dimensions.

Sharma’s book has gained an additional boost through a foreword written by former Chief Justice Kalyan Shrestha. As a judge, Shrestha found Sharma a serious lawyer whose presentations were always “clear, powerful and convincing.” He recommends this book to all those who have an interest in Nepal’s law, justice, and politics.

![Maha Shivaratri being celebrated across the country [With Pictures]](https://en.himalpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/HRB_KTMImage2026-02-15at7.37.40AM1.jpg)

Great book through which one could be benefited in knowing the picture of nation. Good job ! Jay Hos ! Jay Matribhumi !