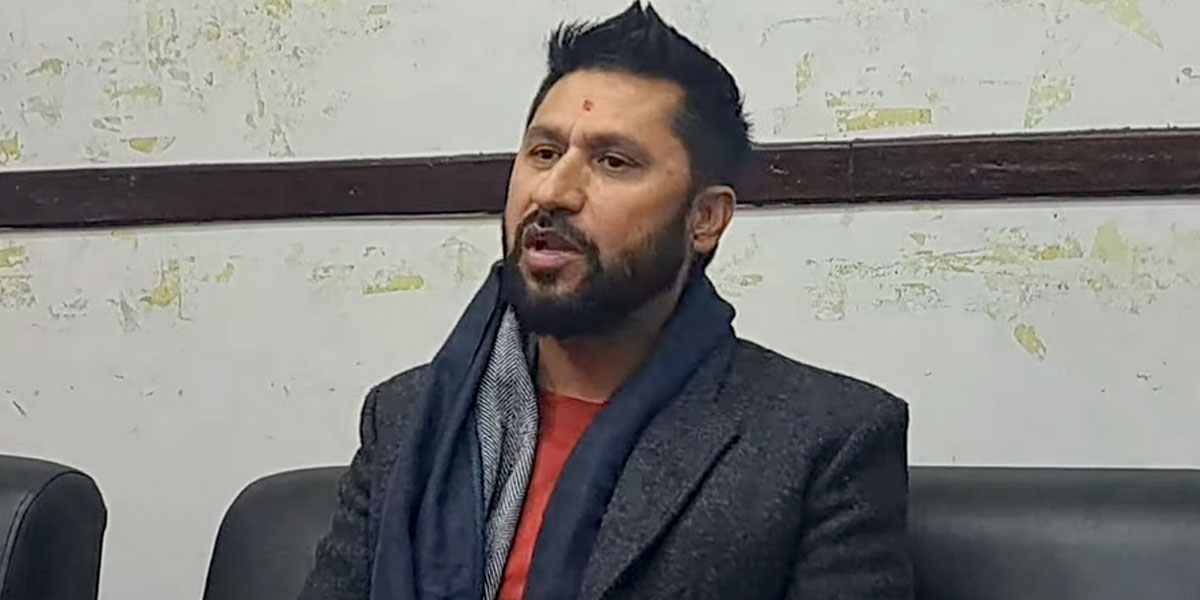

Many actors, such as Dayahang Rai, Saugat Malla, Bijay Baral, Nazir Hussain, Pashupati Rai and Menuka Pradhan, who entered the film industry through theater, have become fan favorites. Audiences enjoy character-driven films featuring these artists. Sulakshyan Bharati is one such personality who entered the film industry after acting and directing in theater.

Bharati has acted in and directed numerous plays. He has successfully brought theater productions to the big screen. Audiences liked his directorial debut film, Boksi ko Ghar (The Witch’s House). He later gained recognition for his acting in the road thriller Bato (Road). His third film, Mummy, is releasing on February 7.

In recent years, Nepali producers and directors have tried different genres. Audiences have also liked these different types of films. This year’s releases like Boksi ko Ghar, Gaun Aayeko Bato, Gharjwai, Khusma, 12 Gaun, Chhakka Panja 5, Purna Bahadur ko Sarangi and Tel Visa – all from different genres – have done well with audiences.

Different styles and contextual stories are adding diversity to films. Movies are being produced and screened in various genres including comedy, social, family drama, horror, action, suspense and thriller. Bharati believes this diversity offers new choices to the audience. “Nepali films need to move beyond traditional genres to excel,” he added.

Talking about diversity in Nepali films at the Thaha Film Festival held recently in Makwanpur, Bharati said while diversity has been seen in Nepali cinema in recent times, getting these films to audiences is challenging. “There are audiences for every genre. Nepali films have embraced diversity. However, reaching the general audience has become a challenge for filmmakers,” he said.

He added that audiences often do not know when “new-genre” films are released and how long they will run in theaters. “The issue is not the lack of audience; it is our inability to reach them effectively. Filmmakers are failing to do sufficient marketing. Also, new filmmakers are facing difficulty in gaining trust,” Bharati said. “Filmmakers are trying to change audience tastes, which is necessary for the industry.”

He added that since established filmmakers have their own brand, people do not readily trust newcomers who experiment with new genres. “That is partly why films of new genres seem less successful. It is like when we go to restaurants – we look at the menu but end up ordering the same momos. We don’t try different tastes. We need to change this, and that process has begun,” he explained.

Bharati urged new filmmakers to create films in genres they are passionate about rather than following successful trends. “You need to be clear about your story and its target market,” he added.

In recent years, filmmakers have been telling stories of various communities, allowing different groups to understand the culture and traditions of the other communities. Some viewers have complained about seeing stories from the same communities repeatedly. Bharati, however, said that Nepali films have always represented society through various classes, ethnicities and costumes.

Some film critics have accused makers of exploiting their cultural poverty while telling stories from the community. Bharati disagrees with this criticism. He argues that no one can fully represent an entire geography from a single perspective, and stories that seem familiar to some might appear novel to others.

“Our familiar stories might seem new to foreigners. While we enjoy the 21st century in one area, it is entirely different when we step outside the Kathmandu Valley,” Bharati said. “It is natural for filmmakers to be attracted to such contrasts. It is normal for audiences to be curious about why such situations still exist. It is not about selling poverty but showing reality. Selling is a very different aspect,” he explained.