Political donations are a common feature of democracies as they support the sustainability of political parties, enabling them to promote their agendas. Such donations also foster a healthy competition of ideas and programs. In some countries, the state directly allocates funds to political parties that meet specific thresholds of popular votes. However, political financing remains a contentious issue globally, often debated for its benefits and drawbacks. Election campaign finance, in particular, is equally controversial, with many political parties advocating for state funding.

To create a level playing field among contesting parties and provide the financial resources needed for their smooth functioning, states enact laws allowing parties to accept donations from well-wishers, followers, and corporate houses. However, while drafting these laws, it is impossible to foresee every potential misuse, leaving grey areas that political parties often exploit. Such laws assume a high level of moral and ethical conduct among political leaders—an expectation that rarely aligns with reality.

In Nepal, the Political Parties Act, 2016, includes provisions governing donations. Clause 38(5) of the act prohibits financial contributions tied to conditional benefits, while Clause 38(6) requires donors contributing more than Rs 25,000 to declare their source and transfer the amount through banking channels.

However, people rarely give away their property or wealth without expecting something in return. Yet, the law expects political donations to be free from conflicts of interest—a notion more suited to the idealistic Satyayuga than the pragmatic Kaliyuga. It is hard to imagine corporate houses contributing voluntarily to political parties without anticipating personal or professional benefits.

In Nepal, pervasive corruption—enabled by a costly electoral system—has slowed economic growth, hindered social transformation, and stunted human development.

Observers also hope for ethical and moral values in politicians, expecting them to adhere to ideological norms. However, sustaining political operations and competing effectively requires financial resources which leads parties to seek funding in ways that compromise these ideals.

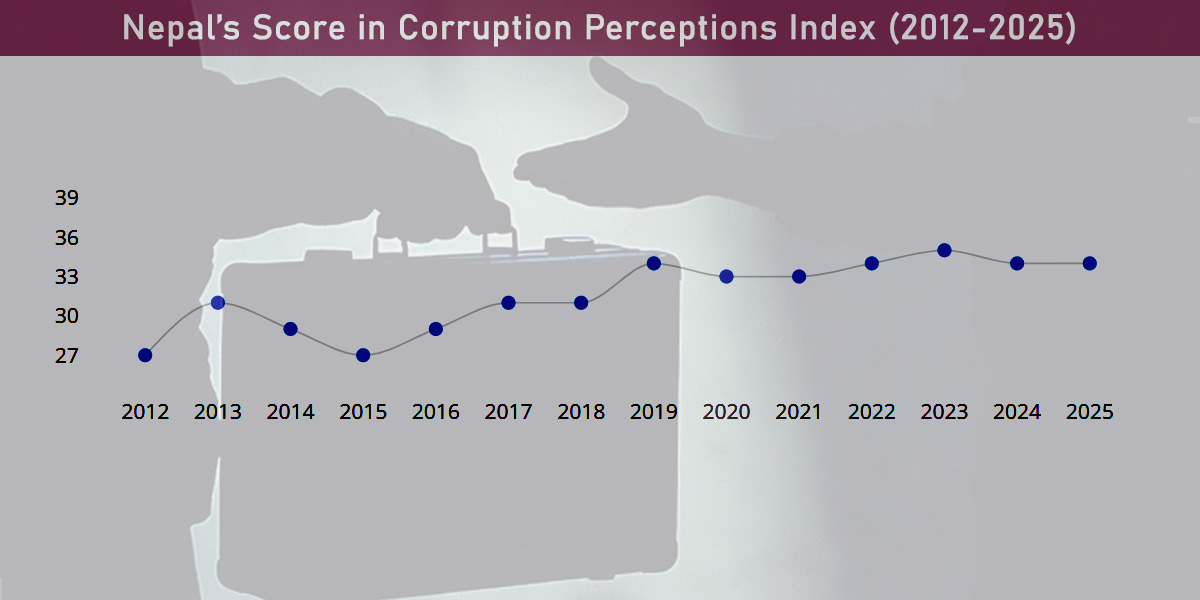

Researches reveal that a decline in ethical values and moral integrity hampers human progress, tarnishes a nation’s image, and exacerbates governance challenges. In Nepal, pervasive corruption—enabled by a costly electoral system—has slowed economic growth, hindered social transformation, and stunted human development.

Two recent cases highlight the contrasting approaches to political donations and governance. In Singapore, former Minister Subramaniam Iswaran was sentenced to 12 months in prison for accepting gifts worth SGD 403,000, including Formula 1 tickets, a luxury bicycle, alcohol, and private jet rides. Singapore’s strict anti-corruption laws view such gifts as corrupt practices and abuses of power.

In Nepal, a business tycoon offered to donate 10 ropanis and 14 anas of land in Maitri Nagar, Kirtipur, to the CPN-UML party. The tycoon also proposed constructing a modern party headquarters valued at Rs 1.5 billion. This offer has raised eyebrows among the public and political observers, questioning whether it crosses the ethical boundaries of governance.

Corruption in Nepal is deeply entrenched, creating a nexus that connects public officials, private entities, and criminal networks. Political donations, often disguised as voluntary contributions, are a tool for gaining influence over decision-makers. Such practices promote cronyism and weaken institutions, obstructing Nepal’s developmental aspirations.

The business tycoon, Min Bahadur Gurung of Bhat-Bhateni Super Market, involved in the recent donation offer has a controversial history. He was convicted in the Lalita Niwas land-grab case and sentenced to two years in prison, along with an Rs 8 million fine.

The unchecked flow of political donations and associated corruption undermine governance, diminish democratic values, and harm Nepal’s international image. The country’s slow economic growth and stagnation in human development are frequently attributed to these systemic issues. Corruption discourages foreign investment and assistance, further impeding progress.

In Nepal, political donations are common and often taken lightly, driven by the perception that such practices, being socially accepted, do not negatively influence governance. However, corruption in Nepal has developed into a deeply embedded web of interconnected stakeholders spanning the public, private and criminal spheres. This nexus is not isolated but intricately interwoven, thriving through horizontal and vertical connections that foster impunity and self-preservation. At the center of this network are political parties and their influential leaders. A recent survey found that leaders, irrespective of their parties or ideologies, are frequently involved in financial irregularities, including cooperative scams. In this sense, Nepal’s political leaders act as patrons of a vertically integrated kleptocratic network that perpetuates cronyism.

Nepal lacks effective legal mechanisms, instruments, and systems to hold political parties accountable for their financial dealings. Surveillance and monitoring agencies that could control unethical behavior within parties are either absent or ineffective. Many experts blame the existing electoral system for fostering unethical financial practices, which they identify as both the cause and effect of policy corruption.

Loopholes in laws and their subsequent misuse for political gain have become a norm among Nepal’s political parties. For instance, the Political Parties Act, 2016, allows parties to accept donations without imposing limits on the amount they can receive. Article 38(1) permits contributions from Nepali citizens and registered corporate organizations. According to the Political Parties Regulations, 2017, contributions exceeding Rs 100,000 require details of the contributor, including their PAN. While these laws mandate auditing, enforcement mechanisms have remained weak.

Corruption’s pervasive presence across sectors obstructs Nepal’s developmental aspirations, undermining the prosperity and the happiness of its citizens. The country’s ambition to transition from a least developed nation to a developing one is at risk if corruption continues unchecked. Recognized globally as a significant impediment to development, corruption is a multifaceted phenomenon with far-reaching causes and consequences.

The traits common to least-developed countries—such as abuse of power, electoral authoritarianism, impunity, social acceptance of corruption, lack of transparency, cronyism, and weak civil society—are visibly prevalent in Nepal. While the degree of these issues may vary, their collective presence undermines the effectiveness of Nepali democracy.

The diminishing integrity of democratic values, rising authoritarian tendencies in governance, and pervasive corruption across all levels of government have undermined Nepal’s credibility

These challenges have eroded public confidence in democracy and federalism. Disillusionment is growing, with many expressing despair over the state of governance. This trend is a troubling sign for a functioning democracy and hinders efforts to institutionalize democratic values. Corruption and political scandals have only increased over time, damaging Nepal’s goodwill, dignity and international reputation.

The diminishing integrity of democratic values, rising authoritarian tendencies in governance, and pervasive corruption across all levels of government have undermined Nepal’s credibility. These issues threaten to derail the nation’s developmental goals and reduce the inflow of foreign assistance and capital investment.

Researcher Sarah Chayes argues that corruption is the primary reason for underdevelopment. Resource-rich countries often fail because corrupt regimes enrich ruling elites at the expense of broader societal progress. This phenomenon, characteristic of failed states, is also evident in Nepal, where a small elite monopolizes economic and social benefits.

There must be stringent measures to regulate the acceptance of political gifts, donations, and favors by officials. It should be mandatory for any such contributions exceeding the legally accepted limit, in either value or kind, to be submitted to the government treasury. Failure to comply with this provision should be explicitly classified as corruption. Furthermore, the law must clearly differentiate between campaign finance and political finance to ensure greater transparency and accountability.

In the current land donation case, the legal framework has left certain grey areas open to interpretation. Rather than assigning blame prematurely, this presents an opportunity to seek a definitive legal verdict on the definitions of donations, gifts, hospitality, and favors, along with the code of conduct for governance concerning financial transactions. While the case is sub judice and the court’s ruling is awaited, from a broader ethical perspective, the actions involved have raised serious questions about accountability.

![Maha Shivaratri being celebrated across the country [With Pictures]](https://en.himalpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/HRB_KTMImage2026-02-15at7.37.40AM1.jpg)